Discover Via Francigena - Museo di San Caprasio

Main menu

Discover Via Francigena

The Via Francigena as Sigeric's itinerary

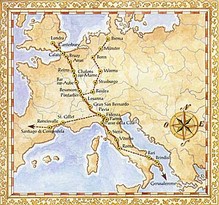

The Via Francigena was the most important pilgrim route in medieval Europe. It starts from Canterbury, runs through the county of Kent till the Channel and then through the French regions of Nord-

The Via Francigena was not a single, well-

However, the Via Francigena finds its unity in the historic route followed by the Archbishop of Canterbury Sigeric in A.D. 990; this track is the target of projects meant to promote tourism and to enhance its great cultural heritage.

In fact, Sigeric's diary is one of the most famous documents which attest the historicalness of the route: on his way back from Rome, where he had been to receive the "pallium" -

The Council of Europe has chosen Sigeric's route, described in a precious manuscript kept in the British Library in London, as the official Way to Rome. The official Via Francigena, therefore, is the one recorded by Sigeric in the tenth century.

History

The Via Francigena : a Bunch of Roads

Which routes did the pilgrims follow to reach Rome, the new Jerusalem? There was plenty of routes (called “romee”) leading to the capital city of Christianity from all over Europe, but one of the earliest ever recorded is the so-

Other fundamental stations on the way were Pavia, the former Lombard capital, Piacenza, an important, strategic point, Fidenza, junction point of the routes which came from the Po plain and the Monte Bardone Pass and, on the Apennines, Fornovo and Berceto. Beyond the Apennines, the route reached Pontremoli and Luni. The decline of the port of Luni, which started in the 8th century, fostered the development of Sarzana, Massa and Pietrasanta, which were firstly situated along the Roman consular road Aurelia and then became strategic points along the Via Francigena.

After Pietrasanta, pilgrims were forced to leave the Thyrrenian coast, which was an unsafe place owing to frequent incursions of pirates, and to take the route which led to Camaiore, Lucca and Altopascio. In the Middle ages, this town offered one of the most well organised hospital for pilgrims of all Europe. After Altopascio the route headed towards Val d’Elsa and Siena. There it joined the consular road Cassia and led to Acquapendente, Bolsena, Montefiascone, Viterbo, Capranica, Sutri and Monterosi. In La Storta, near Rome, pilgrims usually left Via Cassia, which went through unhealthy, dangerous areas, and followed the ancient Via Triumphalis, eventually reaching the Vatican from Monte Mario, called Mons Gaudii (“Mount of Joy”).

Pilgrims usually reached St. Peter’s square from the right flank of the Basilica, coming from Via del Pellegrino – Pilgrim’s road – and from Porta Sancti Pellegrini, along a stretch of road stretch which was called for a long time “ruga francisca” (“road of the French”).

In order to cross the Alps and reach the Italian side of the Via Francigena, pilgrims used to climb Monginevro or Moncenisio Passes, which joined in the town of Susa. Other access points were the Great and the Little Saint Bernard Passes in the Aosta Valley. The Moncenisio Pass was the preferred one by pilgrims, since the Abbey of Novalesa and the Sacra di San Michele are on this way. The Sacra di San Michele, in particular, was built nearby the places where Charlemagne's army had outflanked the defensive line set by Adelchi's army, king Desiderius's son and last Lombard king.

Other fundamental stations on the way were Pavia, the former Lombard capital, Piacenza, an important, strategic point, Fidenza, junction point of the routes which came from the Po plain and the Monte Bardone Pass and, on the Apennines, Fornovo and Berceto. Beyond the Apennines, the route reached Pontremoli and Luni. The decline of the port of Luni, which started in the 8th century, fostered the development of Sarzana, Massa and Pietrasanta, which were firstly situated along the Roman consular road Aurelia and then became strategic points along the Via Francigena.

After Pietrasanta, pilgrims were forced to leave the Thyrrenian coast, which was an unsafe place owing to frequent incursions of pirates, and to take the route which led to Camaiore, Lucca and Altopascio. In the Middle ages, this town offered one of the most well organised hospital for pilgrims of all Europe. After Altopascio the route headed towards Val d'Elsa and Siena. There it joined the consular road Cassia and led to Acquapendente, Bolsena, Montefiascone, Viterbo, Capranica, Sutri and Monterosi. In La Storta, near Rome, pilgrims usually left Via Cassia, which went through unhealthy, dangerous areas, and followed the ancient Via Triumphalis, eventually reaching the Vatican from Monte Mario, called Mons Gaudii ("Mount of Joy").

Pilgrims usually reached St. Peter's square from the right flank of the Basilica, coming from Via del Pellegrino -

The Via Francigena, an artery for commercial trades and pilgrimages, became a very important communication route between Northern and Southern Europe and a fertile soil for cultural exchanges. Monuments and art treasures spread in the main towns along the route: wonderful cathedrals, such as Lucca, Sarzana or Fidenza and churches which held precious relics, such as those that are in the crypt of the Cattedrale del Santo Sepolcro (Cathedral of the Holy Sepulchre) in Acquapendente, brought there -

Sanctuaries and oratories dedicated to the Patrons of pilgrims -

A common European civilisation has its roots in the Via Francigena as well as in Saint James's Way. For these reasons, the Via Francigena was awarded "European Cultural Route" by the Council of Europe in 1994, just like Saint James's Way, which leads to the tomb of Saint James the Apostle, defender of Christianity.

text edited by Associazione Culturale Jubilantes

articolo e foto fornite gentilmente da "www.viafrancigena.eu" -